History

A Thriving Business District

Situated in downtown Oakland, California, Old Oakland is comprised of 10 historic buildings that date back to the 1860s. This unique offering of retail and office space provides a historic setting with thoroughly modern amenity that is close to San Francisco and is conveniently located in the Bay Area.

Old Oakland is located within the Downtown Business Improvement District (BID)with its ambassadors on the street, ongoing marketing efforts and other activities.

The History of Old Oakland

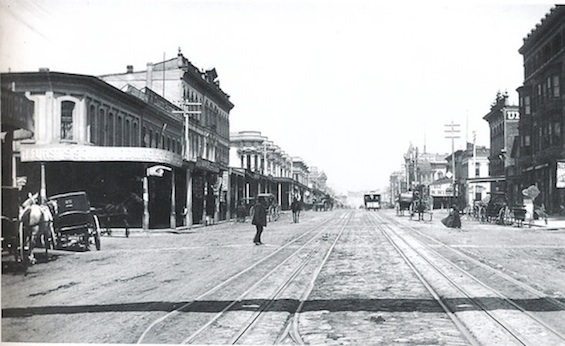

The history of Old Oakland begins in the late 1860’s, when the Transcontinental Railway opened its western terminus in Oakland, on Third Street near Broadway. This event marked the beginning of the move of the City’s central district away from the waterfront, and northward along Broadway. The prosperity brought by the Railway began a cycle of growth for Oakland which resulted in the commercial hub of the City being firmly established at Ninth Street and Broadway by 1877.

During the late 1800s Old Oakland was the place to be. It was in this neighborhood that City parades began and ended. Old Oakland was home to the City’s best hotels (boasting the luxury of grand ballrooms and “modern,” semi-detached washroom corridors), offices, stores and elegant restaurants. The neighborhood could offer the prosperous businessman prime property, grand shops, a thriving fresh-food market, and the most modern amenities. Old Oakland became home to fine established businesses operated by wealthy entrepreneurs.

However, just as development away from the waterfront had created the commercial nucleus at Ninth Street, the continuation of that growth eventually relocated the City’s center still farther northward, at Broadway and Fourteenth Street. By the turn of the century, the grand shops and the leading businessmen, many of whom had been the City’s founders, were gone from Old Oakland. The neighborhood remained an important center for more modest commercial activity until the end of World War II, when most major U.S. cities experienced the “flight to the suburbs” syndrome. It was then that the Old Oakland neighborhood began its decline.

For the next thirty years the finest collection of historic buildings in the West deteriorated so badly that some of the structures had to be condemned. A stranger walking those littered streets would never have guessed that a once elegant history was buried beneath the buildings’ neglected and tattered facades.

Historic Restoration of Oakland's Crown Jewel

When architects Glenn and Rich Storek first discovered Old Oakland in the late 1960s they immediately saw the intrinsic quality in these neglected but still beautiful Victorian buildings. They were determined to save them from any foreseeable wrecking ball and restore them to their former grandeur. It took almost fifteen years to acquire, renovate, and meticulously restore Old Oakland to its former glory. The major reconstruction included earthquake resistant structural work and modern mechanical and fire sprinkler systems. Special care was taken to restore the buildings’ facades and interior cores to their original splendor. Much of the Victorian interior features have been preserved, such as grand, sweeping staircases, delicate skylights, and ornate period mouldings. Dozens of architects, historians, designers, crafts persons, and artisans worked for several years to complete these renovations. Thanks to the support of the City of Oakland’s Redevelopment Agency, many of the public spaces were improved, included repaved streets, cobblestone gutters, brick sidewalks, and historic street lamps.

Oakland’s Famous “Water Wars” on the Leimert Block of Old Oakland

Two of the more notable tenants that occupied the Leimert Block were Anthony Chabot’s Contra Costa Water Company offices and the office of real estate tycoon, William J. Dingee.

The Contra Costa Water Company moved into the Leimert Block as soon as the building was completed in 1874.

Anthony (spelled as “Antone” in the City Directories), Chabot, a native of Quebec, organized the Contra Costa Water Company in 1866. His company was the first to successfully deliver piped water into Oakland. At that time, wells were Oakland’s primary water source. In 1858, Chabot had delivered San Francisco’s first public water from a creek near the Presidio. Chabot began laying water pipe up Broadway from the Estuary in December, 1866, and by June, 1867, water was carried through the pipes from Temescal Creek, the quality of the water was often poor. In 1867 the Daily Morning Journal wrote: “The water obtained from the mains of the Contra Costa Water Company last evening was quite muddy and almost unfit for household purposes. Water from almost any well was superior”. The quality and supply of water was somewhat improved after Chabot completed Temescal Dam and the present Lake Temescal in 1869, although shortages still abounded, especially during the summer months. An additional source of supply was obtained in 1876, after Chabot gave up his absolute control of the water company, although he remained as president for several more years.

William J. Dingee is first listed in the City Directories in 1877-78 as a “bookkeeper” with Olney and Company. He first appears in the Leimert Block in 1881-82 as a partner in the firm of Taggert and Dingee, “real estate and general auctioneers”, occupying the spaces at 460 and 462 8th Street. Dingee had advertised in 1885 that having “long resided in Oakland” he could offer homes “at all prices, from neat little tasty cottages at $1,500 to the more pretentious residences at $3,000 to $5,000, or the elegant mansion at $10,000 and upwards.”

In 1886-87, Dingee began to be listed by himself at this location. He seems to have been quite resourceful in his business, his principal activity apparently having been land auctions. By 1887, he was successful enough to construct his lavish “Fernwood” mansion and estate, in the present Montclair area. The estate included a deer and game preserve.

Both Dingee and the Contra Costa Water Company continued to occupy their adjacent offices in the Leimert Block until the mid-1890’s, when they became ruthless adversaries during the celebrated “Water War”. The water war started when the water company turned down a service request by Dingee. He had wanted the water to develop some of his acreage in the Montclair – Piedmont area. The refusal seems to have been due primarily to the company’s continued supply problems. Dingee responded by drilling tunnels into the hills on his estate above Shepherd Canyon to tap underground water sources. In order to pay for this costly venture, he extended his pipes beyond his Piedmont property and into the Oakland flatlands, portions of which were still poorly served by the Contra Costa Water Company, and forming in 1893 the Oakland Water Company. This placed him in direct competition with the Contra Costa Water Company.

The competition soon became fierce. Both companies hired experts to analyze each other’s water and to declare it unfit for human consumption, results which they then loudly publicized. Holes were bored into Contra Costa Water’s marshland flumes, so that brackish water contaminated its supply for several days, and a City sewer was found hooked onto one of it mains, incidents which were blamed on the Oakland Water Company. Oakland Water claimed that someone was pumping millions of gallons of fresh water out of its Alvarado Wells into the bay. Dingee exclaimed, “The Contra Costa Water Company has hired newspapers to libel me…They have lied about the quality of our water…(and have) pumped lime into our lines….” He also accused Contra Costa Water of cutting and blowing up his mains. The war resulted in severe water shortages. It became impossible to get water into the upper floors of downtown buildings in the afternoon. Pitchers had to be used to carry water to the second floor of City Hall. Mayor Thomas urged that the two companies consolidate and he threatened to form a municipally-operated water company to take over their service, but Contra Costa initially refused to consider consolidation. Finally, in 1898, the City initiated formation of a municipal waterworks, which apparently induced the warring companies to merge under the name of the Contra Costa Water Company, but with Dingee in control.

Although Dingee and the Contra Costa Water Company remained neighbors in the Leimert Block at the start of the water war, by 1895 the Contra Costa Water Company had moved into the Blake and Moffit Block at the northeast corner of 8th Street and Broadway, its Leimert Block office being taken over by Dingee’s Oakland Water Company. By 1899, after Dingee had gained control of Contra Costa Water, both operations relocated to the adjacent building whose address is now 801-7 Broadway. At the end of the war, Dingee was a millionaire. After his Fernwood mansion was destroyed in an 1899 fire, he moved to 1882 Washington Street in San Francisco, his residence being known as the “diamond palace”, and bought two mansions on New York’s 5th Avenue which cost $1 million each. He gained control of the slate roof industry, started cement plant projects in California, Pennsylvania and Washington and became a San Francisco park commissioner. When San Francisco’s corrupt Mayor Eugene Schmitz got into legal trouble, Dingee put up a $200,000 bond for him.

However, about 1908, Dingee’s empire crashed and he lost virtually everything. He entered bankruptcy court in 1921 and died in obscurity in 1941.